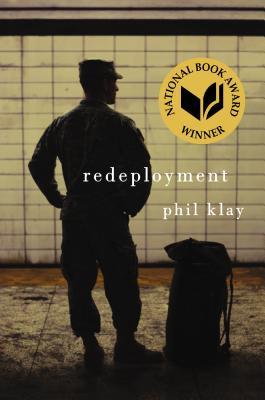

Yet, simultaneously, I happened to be reading Phil Klay's National Book Award winning collection of short stories, "Redeployment," about the Iraq war and its aftermath. It helped to put my thoughts into perspective. My brother has a glorious legacy, a wife who will always love him, four wonderfully unique children, and six amazing grandchildren.

What if, I wondered, his life had veered down a very different path back in the late '60's, early '70's when the draft lottery was implemented. How well I remember the night my college buddies and I hung breathless in front of the TV watching our futures be determined by a rolling metal basket full of numbers. The Vietnam War was raging. Some would go halfway across the world to fight a battle they didn't even believe in based upon the fluke of a glass capsule in a cage. My brother was spared.

Not so fortunate are the boys Klay introduces us to. One could say that the difference is that these kids signed up. Full of the jingoistic passion that permeated the country after the Sept. 11th attacks of 2001, 18-year-olds were falling over themselves to join the Marines. Or were they? As Michael Moore pointed out so eloquently in his film, Fahrenheit 9/11, those who go to war today can often be lottery losers as well. Today's lottery is a matter of economics. Those with advantages stay home and get more advantages. Those without, go to war.

The strongest story in the collection is undoubtedly the first, the title story, "Redeployment." It's a heartbreaking rendering of a soldier returning to the states after a nine month tour in Iraq and the stream of consciousness thought process he goes through as he contemplates the reunion with his wife and their dog. The awkwardness as husband and wife try to avoid any serious conversation, plying each other with platitudes, is palpable. When he takes her to their bed he sees, just for a split second, fear in her eyes.

Phil Klay served in Iraq after graduating from college. He admits in interviews that he never actually was in a dangerous position. Yet he manages to capture the chaos of war and the bitter irony of the manner in which our government conducts war. Another story, "Money as a Weapons System," reads like "Catch-22," when a new foreign service officer is charged with rebuilding a water treatment facility (that we had destroyed, of course) with money earmarked for a women's health facility that was hugely successful.

And in "War Stories," a horrifically burned, deformed young man named Jenks meets with his best friend in a bar where they have a surreal conversation about how to get Jenks laid without having the woman pity him. Later, a girl joins them who is doing research for a veterans' film project. She asks pointed, seemingly heartless questions of Jenks about his injuries, how it happened and what he felt afterwards, yet Jenks handles these with aplomb. It is his friend, angry and defensive, who loses it.

I have read some provocative, excruciating, powerful novels about war. Karl Marlantes' "Matterhorn," will always stand out as the finest depiction of the Vietnam War for me. And though I don't think that Phil Klay's short stories have the cohesion I'd like to see in a series, I suspect that they will be remembered, along with other Iraq war classics like "Billy Lynn's Long Half-time Walk," or "The Yellow Birds," as a fine example of the deeply personal and profound literature coming from our veterans. We owe them a reading to bear witness to their bravery, confusion, and pain, and to accept partial responsibility for sending them off to war in the first place.

No comments:

Post a Comment